By Kunle Oshobi

In what critics are calling a devastating blow to Nigeria’s electoral integrity, the Nigerian Senate has rejected proposals to make the electronic transmission of election results mandatory, opting instead to retain ambiguous language that leaves critical loopholes open for potential manipulation ahead of the 2027 general elections.

During the clause-by-clause consideration of the Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2026, the Senate voted down a proposal to compel presiding officers of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) to electronically transmit results from polling units to the IReV portal in real time. Instead, lawmakers retained the existing provision from the Electoral Act 2022, which states that results shall be transferred “in a manner as prescribed by the Commission”, language that is deliberately vague and permissive rather than mandatory.

The Critical Distinction That Changes Everything

The controversy centres on a deceptively simple question: Should electronic transmission be mandatory or merely permissive? This seemingly technical distinction carries profound implications for democratic credibility. The 2022 Electoral Act’s language is permissive, not mandatory. It allows INEC to transmit results electronically but does not require it. More critically, it gives INEC discretion to determine the manner of transmission, creating a grey area that the Supreme Court exploited in October 2023 when it ruled that electronic transmission was not mandatory and that INEC’s IReV portal had no legal status as a collation system.

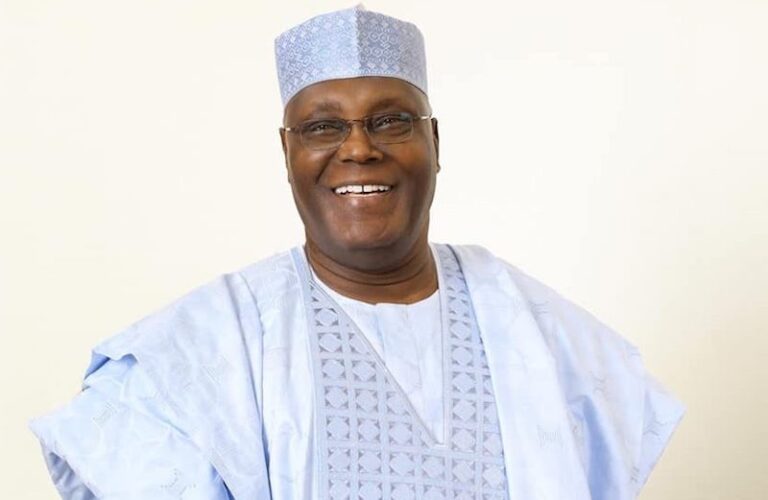

That Supreme Court ruling proved decisive in dismissing the 2023 presidential election petitions and affirming President Bola Tinubu’s controversial victory, a judgment that exposed the legislative lacuna that many Nigerians hoped this amendment would finally close.

A Betrayal of Public Trust

Nigeria’s major opposition parties, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), African Democratic Congress (ADC), and New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP) have condemned the Senate’s action as a “betrayal of public trust” and a dangerous rollback of democratic gains. “They know Nigerians are fed up with them,” the parties stated. “They are aware of the rejection that awaits them at the forthcoming polls. A free and fair election has therefore become a threat to them. This is why they have to preserve and protect any loopholes that could aid the manipulation of the electoral process to their advantage.”

This accusation gains weight from a glaring inconsistency: The same APC that rejects mandatory electronic transmission of election results is currently deploying technology to run an e-registration of party members across the country. If technology is good enough to register party members, why is it not good enough to be made mandatory for transmitting election results?

The Lessons of 2023 Ignored

The 2023 general elections should have been a watershed moment for electoral reform. INEC deployed the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) and promised that results would be transmitted electronically to the IReV portal in real time. What happened instead was widespread controversy. Results were not transmitted promptly. The IReV portal experienced mysterious glitches. When legal challenges reached the courts, the judiciary ruled that the electronic transmission was never mandatory, and that INEC’s failure to upload results in real time did not invalidate the election.

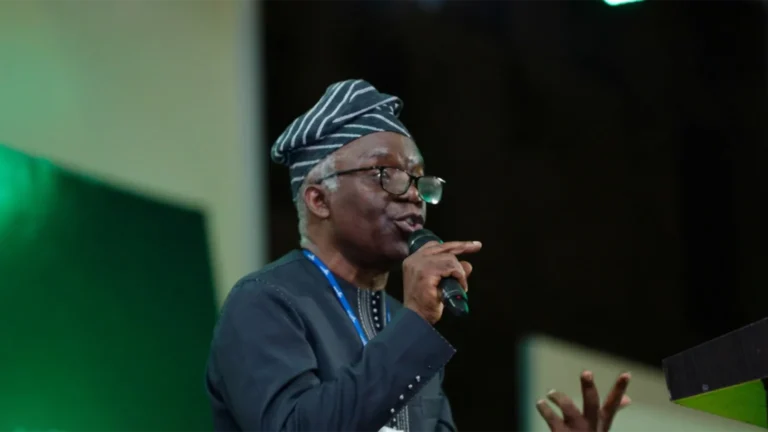

“What, then, are lawmakers amending in the 2022 Electoral Act if the very clause required to improve transparency and credibility in our electoral process is deliberately rejected?” the Labour Party asked. If the amendment process is not closing the loopholes exposed by 2023 and affirmed by the Supreme Court, what is its purpose?

A Global Standard Nigeria Refuses to Embrace

Nigeria’s resistance to mandatory electronic transmission stands in stark contrast to electoral reform across Africa. Several African countries have successfully adopted electronic transmission of election results, demonstrating that the technology is neither untested nor unreliable.

Kenya has pioneered the Kenya Integrated Election Management System (KIEMS). In the 2022 general elections, more than 80 percent of presidential result form images were transmitted electronically by midnight, with the publication rate exceeding 99 percent. Despite controversies around other aspects, the European Union Election Observation Mission noted that electronic transmission enhanced transparency, as results forms were uploaded at the polling unit level and could be checked online.

Zambia’s Electoral Commission has successfully implemented electronic transmission of election results. International observers from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) cited electronic transmission as one of the “best practices” contributing to polls that were declared “peaceful, transparent, credible, free, and fair.”

Ghana, often praised as West Africa’s most stable democracy, has conducted multiple elections with transparent result management, including online publication of results that enhances public confidence. South Africa’s Independent Electoral Commission has been exploring advanced e-voting technologies and real-time result transmission systems. Sierra Leone has also deployed electronic result tallying systems to improve the speed and accuracy of result computation.

These examples demonstrate that electronic transmission is not some futuristic fantasy but a present reality that has improved electoral processes across Africa. When implemented with proper safeguards, it reduces human interference, limits result manipulation, and ensures that the will of voters is faithfully reflected in final outcomes.

Preparing the Ground for 2027?

The timing of this decision raises troubling questions. With the 2027 general elections approaching, the Senate’s rejection of mandatory electronic transmission looks less like principled policy-making and more like strategic positioning. By retaining the ambiguous language from the 2022 Act, language that the Supreme Court has already interpreted in the narrowest possible way, the Senate has effectively ensured that similar controversies can arise in 2027.

Results can be transmitted electronically or not, depending on INEC’s discretion. The IReV portal can be used or ignored, again at INEC’s discretion. And if legal challenges arise, the courts can once again cite the lack of mandatory language to dismiss petitions. This is not speculation. This is exactly what happened in 2023. And by refusing to close these loopholes, the Senate has created the conditions for it to happen again.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The ball now rests with the conference committee tasked with harmonising the Senate and House of Representatives versions of the Electoral Act amendment. The House has already endorsed mandatory real-time electronic transmission of results. The question is whether the committee will side with transparency or with ambiguity.

Real-time electronic transmission of results is not a partisan demand. It is a democratic safeguard. It reduces human interference, limits result manipulation, and ensures that the will of the voter, expressed at the polling unit, is faithfully reflected in the final outcome. To reject it is to signal an unwillingness to submit elections to public scrutiny.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. The country can join the growing list of African nations that have embraced transparent, technology-enabled elections. Or it can remain trapped in a cycle of disputed results, court battles, and diminishing public confidence in democratic institutions.

The Senate has made its choice. With 2027 approaching, the stakes could not be higher. Without mandatory electronic transmission, Nigeria’s electoral future looks disturbingly like its past: opaque, contested, and vulnerable to manipulation. Only those bent on rigging the process will scorn reforms aimed at strengthening electoral integrity. The Senate’s rejection speaks volumes about its priorities. And unless Nigerians demand better, loudly, persistently, and unambiguously, those priorities will shape the 2027 elections and beyond.

Kunle Oshobi is the Head of Strategy and Planning of The Narrative Force