Nigeria today no longer merely groans; it bleeds. To reflect on the condition of our beloved country under the All Progressives Congress is to stare unflinchingly into a mirror cracked by hunger, fear, and betrayed hope. This is not a partisan lament; it is the collective cry of a people stretched beyond endurance, a nation where survival has become a daily contest and dignity a distant memory.

Travel across the country and the stories repeat themselves with numbing familiarity. In a roadside market in Ibadan, a woman who once sold garri with pride now measures cups with trembling hands, apologising to customers for prices she neither controls nor understands. “Na government matter,” she says quietly, as though even the truth now must be whispered.

In Kaduna, a commercial driver parks his vehicle not because he is tired, but because fuel costs have turned movement into a luxury. In Aba, a small manufacturer locks his workshop by noon, calculating that the electricity bill, generator fuel, and taxes will swallow whatever profit the day might offer. These are not isolated tales; they are the shared autobiography of millions of Nigerians under APC rule.

While the masses ration hope, a narrow elite feasts without shame. Overnight billionaires sprout from the soil of political patronage. Idle contractors, whose only industry is proximity to power, parade obscene wealth in a country where graduates hawk sachet water and pensioners die queuing for entitlements. The contrast is not merely immoral; it is obscene. A nation built on the sweat of the many has been converted into a playground for the few.

Even more tragic is the army of defenders who polish chains and call them jewellery. Boot-lickers and crumbs-pickers, drunk on proximity to power, have abandoned conscience for convenience. They insult suffering citizens in the name of loyalty, mock hunger as “patience,” and dress incompetence in the borrowed robes of propaganda. Their voices are loud, but empty, echoing nothing except the fear of losing access to crumbs from a collapsing table.

The economy, once bruised but breathing, now staggers like a wounded giant. Prices rise faster than wages can chase them. Food inflation has turned kitchens into theatres of despair. Parents skip meals so children might eat. Students abandon dreams because fees have become fantasies. Hospitals now demand deposits before compassion, while insecurity spreads from forests to highways, mocking official assurances of control.

This suffering has surpassed even the darkest days Nigerians endured in recent memory. What confronts us now is not temporary hardship; it is systemic cruelty. It is governance divorced from empathy, policy severed from human consequence.

Yet history teaches us that nations do not perish merely from bad leadership; they perish when good people surrender to despair. This is the moment for collective awakening. The Nigerian masses must recognise their shared pain as shared power. Hunger knows no tribe. Insecurity respects no religion. Poverty spares no region. Our suffering has unified us more than any slogan ever could.

In moments like this, nations do not require magicians; they require leaders with experience, breadth, and the moral patience to rebuild trust. Nigeria needs steady hands, not experimental bravado; inclusive vision, not sectional triumphalism.

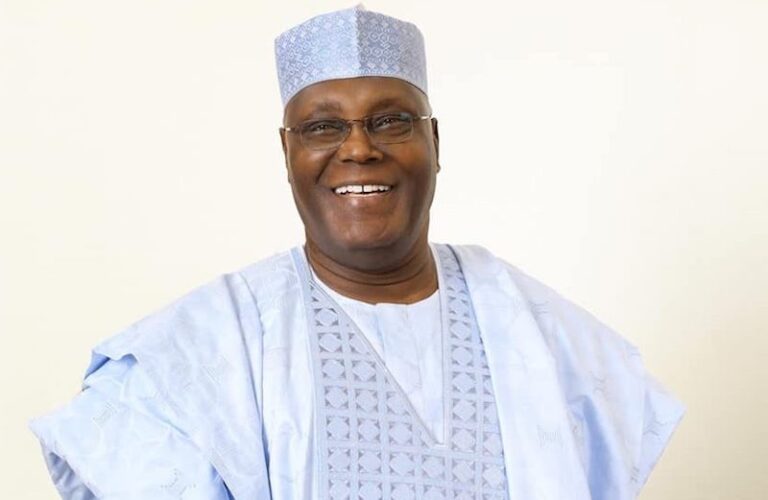

It is also important to remind ourselves that competence is not an abstract promise in Nigeria’s history; it has been witnessed before. During the years when Alhaji Atiku Abubakar served as Vice President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the country recorded one of its most coherent periods of economic coordination, privatisation reform, debt relief negotiation, and investor confidence.

That era was not perfect, but it demonstrated that Nigeria can be managed with policy discipline, federal balance, and economic literacy. That institutional memory matters now, when improvisation has replaced planning and slogans have displaced strategy.

One of the clearest illustrations of that competence was the telecommunications revolution. Before that period, communication in Nigeria was a privilege, not a utility. Telephone lines were scarce, fixed, and controlled; applying for a landline took years, connections were unreliable, and entire communities lived cut off from timely information, emergency contact, and economic opportunity.

Under the reform-driven policies of that era, the telecoms sector was liberalised, competition was introduced, and mobile telephony exploded across urban and rural Nigeria alike. Millions of Nigerians gained access to communication for the first time, businesses were born, jobs were created, and connectivity became a driver of growth rather than a symbol of exclusion. That transformation did not happen by accident; it happened because policy met vision, and leadership understood how reform improves daily life.

It is in this context that Alhaji Atiku Abubakar stands not as a messiah, but as a rallying point for national recovery, a symbol of competence, bridge-building, and economic understanding forged through decades of public engagement.

The call before us is simple but urgent: Nigerians must rise beyond fear, beyond propaganda, beyond manufactured divisions, and unite behind a credible alternative. Silence now is complicity. Apathy is surrender.

Let our tears become testimony, and our anger become organisation. Let the voices from the markets, the campuses, the farms, and the motor parks converge into one unmistakable demand: good governance, accountability, and humane leadership.

In unity lies our redemption. In courage, our restoration. And in collective resolve, the rebirth of a Nigeria where hope is not rationed, labour is rewarded, and leadership remembers the people it was sworn to serve.

But even as this national suffering unfolds in plain sight, another layer of tragedy deepens the wound, one that is more disturbing than hunger itself, because it lives in the mind rather than the stomach.

A friend said something to me this morning that refused to leave my mind. He spoke, not with anger, but with a quiet sadness that cuts deeper than rage. He described the lives of some of the very people who daily storm my social media pages to insult me, to deride Alhaji Atiku Abubakar, and to defend with near-religious zeal a government that has turned suffering into state policy. He spoke of their lives, battered, broken, and threadbare, and the picture he painted was nothing short of tragic.

These are men whose lives poverty has claimed as permanent residence. Men whose mornings begin with hunger and whose nights end in unpaid rent. Men who know the sound of generators better than the hum of electricity, who measure fuel in bottle caps, who postpone hospital visits because pain is cheaper than treatment. Men who argue ferociously online while their children are sent home from school for unpaid fees. Men whose shoes are worn thin by joblessness, yet whose tongues remain sharp in defence of those who authored their misery.

One would imagine that suffering sharpens clarity. But here lies the cruel irony of our time: hardship has not merely impoverished many Nigerians; it has hypnotised them.

I have seen them. The roadside vendor who types abuse under borrowed data while his stall records no sales by noon. The unemployed graduate who quotes government talking points while begging friends privately for transport fare. The civil servant who defends policy on Facebook in the afternoon and borrows money for garri at night. Their lives are collapsing in slow motion, yet they clap. They cheer. They defend.

This is not loyalty; it is psychological captivity.

Under the APC, suffering has been democratised. Hunger no longer discriminates. Food prices mock salaries. Transport costs punish movement. Electricity has become folklore. Healthcare now demands cash before compassion. Insecurity prowls unchecked, while official statements perform gymnastics on television. Parents skip meals. Youths abandon dreams. Old men count medicines they can no longer afford. Yet amid all this, there are still those who rise daily to shield the very system grinding them into dust.

What kind of governance produces hunger and applause at the same time?

This is the most dangerous suffering of all, not the one that empties the stomach, but the one that empties reason. A suffering that convinces its victims that pain is patriotism and endurance is achievement. A suffering that teaches the poor to fight one another while the architects of their misery dine in comfort.

These people must be rescued, not mocked. They must be saved, not scorned. For they are casualties twice over: first of bad governance, and second of manipulated consciousness.

Nigeria does not need citizens trained to clap in chains. It needs citizens restored to dignity, clarity, and hope.

That is why the coming moment matters.

Alhaji Atiku Abubakar represents more than a political alternative; he represents rescue from this national hypnosis. Rescue from economic illiteracy masquerading as policy. Rescue from governance without empathy. Rescue from a system that thrives on the confusion of the poor and the silence of the wounded.

Atiku is coming not for the elites alone, but for the battered defender of his own oppressor. For the hungry man arguing for hunger. For the suffering woman applauding suffering. For the youths gaslit into believing that pain is progress.

The Nigerian masses must be saved, including those who do not yet realise they need saving.

History will not be kind to those who defended agony. But it will remember those who insisted, even when insulted, that a better Nigeria is possible.

Liberation begins with clarity. Rescue begins with courage. And the rescue mission has already begun.

Aare Amerijoye DOT.B.

Director General,

The Narrative Force

/ Feb 10, 2026