Aare Amerijoye DOT.B

There is something profoundly ironic about power that trembles before transparency. It is the paradox of authority that celebrates victory yet hesitates at verification. If you are confident of the mandate of the mandate of the people, why resist the mirror that reflects it instantly, mercilessly, and without backstage editing?

Nigeria stands at that crossroads again, not merely as a republic debating procedure, but as a wounded democracy asking whether its vote belongs to the voter or to the journey after the vote.

The debate over mandatory real time electronic transmission of election results is no longer a technical matter. It is a moral one. It is no longer about bandwidth or servers. It is about courage. It is about whether those who govern us believe in the supremacy of the voter or merely in the arithmetic of collation rooms where numbers sometimes travel farther than ballots.

The proposal to make electronic transmission compulsory should have been the easiest reform to pass in a democracy that claims confidence in its popularity. Instead, the reluctance from the ruling establishment speaks louder than any speech on the Senate floor. Silence, in moments like this, becomes a confession without words.

Bola Ahmed Tinubu presides over a government whose party boasts of commanding political dominance across the federation. The ruling All Progressives Congress controls the federal government and governs the majority of states. By their own narrative, they are the most formidable political machine in contemporary Nigerian history, invincible in rallies, thunderous in propaganda, confident in arithmetic.

And yet, when asked to make the transmission of results from polling units mandatory and instantaneous, hesitation creeps in like a shadow entering a brightly lit room.

Why?

If a party controls about thirty governors, if it claims grassroots penetration, if it insists it enjoys overwhelming public support, should it not be the loudest advocate for instant electronic transmission? Should it not be eager to prove that its victories are so decisive that they can withstand the glare of real time digital scrutiny before the entire nation and the watching world?

Or is confidence only loud in rallies and cautious in legislation?

Allow me a story.

There was once a village wrestling champion who insisted he was unbeatable. Every market day he paraded through the square recounting his triumphs, reminding villagers of how many opponents he had flattened. Drummers announced his dominance before he even arrived. Children were taught to chant his name as if defeat were a myth.

One afternoon a boy approached him and said, Great champion, since you are undefeated, why not wrestle in the town square at noon instead of in the evening shadows?

The champion coughed. He spoke about dust. He spoke about heat. He spoke about how sunlight can be distracting. He spoke about how the ground is uneven at noon but somehow perfect at dusk.

The villagers understood. Strength that negotiates with sunlight is strength that knows something about the dark.

Strength that fears daylight is not strength. It is theatre.

Today the ruling establishment assures Nigerians that it commands the political landscape. Governors are counted like medals. Structures are invoked like fortresses. The confidence is theatrical and repetitive, repeated so often that it begins to sound like self reassurance.

Yet when the proposal arises that every polling unit result be uploaded instantly and irreversibly for the entire nation to see, the drums grow softer. The thunder becomes grammar. The swagger becomes syntax.

Picture another scene.

A private gathering in the capital. Governors seated comfortably, laughter flowing, speeches about landslides and loyalty. Then someone raises a toast and suggests, Let us make electronic transmission mandatory so that every victory appears nationwide within minutes, beyond dispute, beyond midnight arithmetic.

The laughter pauses.

One governor suddenly remembers network challenges in rural areas. Another speaks of infrastructure limitations. A third recommends flexibility. The word mandatory begins to sound like a constitutional earthquake.

Curious.

The same rural communities conduct mobile banking, register SIM cards, stream campaign songs, trade online and send digital donations. The same villages upload campaign posters, receive political broadcasts, and transfer funds in seconds. Technology is reliable when revenue is to be collected. It becomes fragile when transparency is to be enforced.

This is not a technological contradiction. It is a political one.

The Senate’s resistance to mandatory transmission, under the leadership of Godswill Akpabio, raises unavoidable questions. When ambiguity is defended more passionately than clarity, citizens are entitled to ask what exactly that ambiguity protects, and whom it comforts.

The current legal language leaves electronic transmission to the discretion of Independent National Electoral Commission. Discretion sounds harmless until it becomes selective application. A safeguard that is optional is not a safeguard. It is a suggestion politely waiting to be ignored when it matters most.

Let us speak plainly.

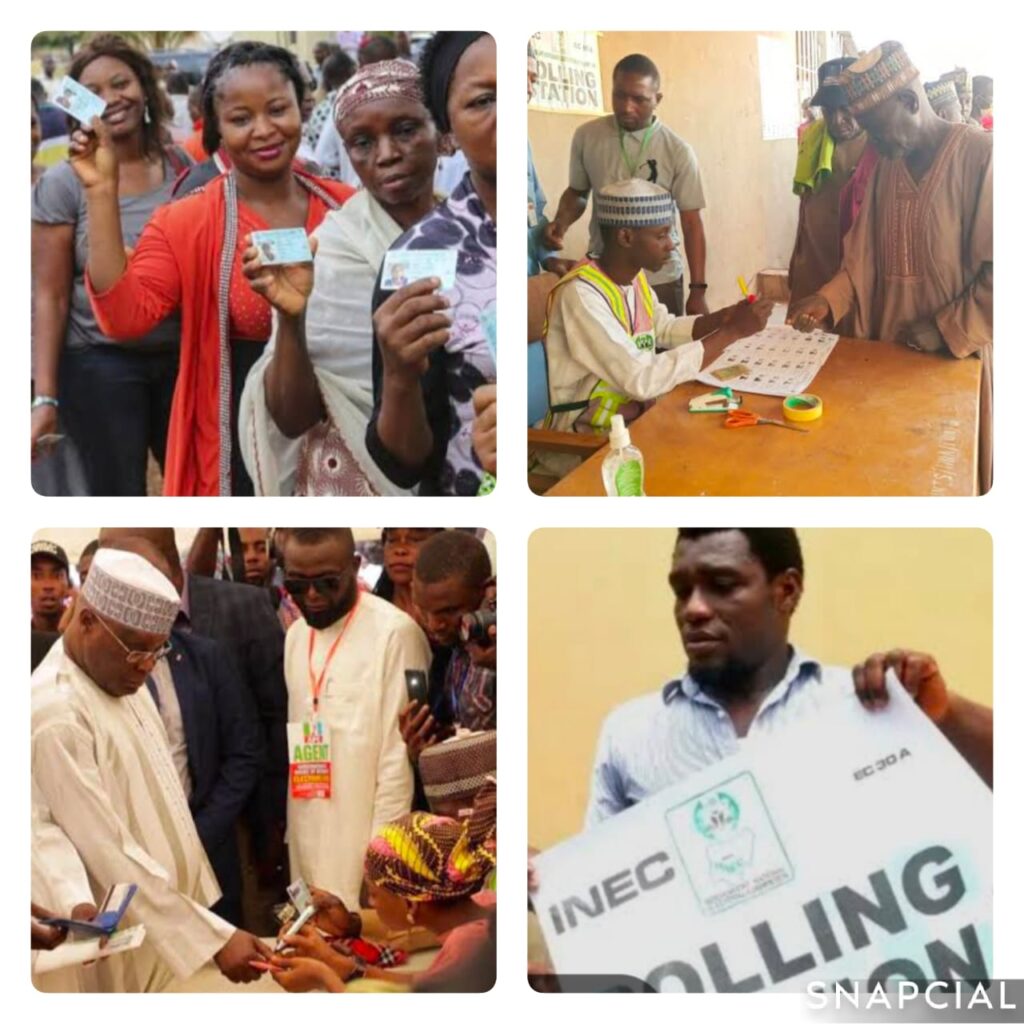

Mandatory transmission eliminates the dark corridor between polling units and collation centres. That corridor has historically been the most controversial stretch of Nigeria’s democratic highway, the place where trust often disappears before results arrive.

It reassures voters who stand under the sun for hours that their decision will not evaporate in transit. The voter who waits eight hours in heat deserves to see his vote online in eight minutes. Democracy should not depend on suspense or on journeys through invisible rooms.

It reduces post election litigation and distrust. Transparency does not weaken winners. It legitimises them, fortifies them, crowns them with credibility that no court challenge can easily shake.

And this is where satire becomes uncomfortable truth.

If the ruling party truly commands thirty governors and enjoys organic grassroots dominance, then mandatory instant transmission should be its proudest reform. It should be the reform it champions with applause. It should declare to Nigerians, We are so confident of victory that we welcome the speed of light, we welcome scrutiny, we welcome evidence.

Instead, caution is dressed up as prudence. Delay is dressed up as flexibility. Ambiguity is dressed up as wisdom.

One is tempted to ask, is the party no longer comfortable with governors winning elections? Is numerical advantage insufficient without procedural fog? Has dominance become allergic to daylight? Has power grown uneasy with mirrors?

In every marketplace there is a simple principle. The trader who is certain of the weight of his goods invites the scale. He does not negotiate with gravity. He does not argue with measurement. He does not ask the scale to blink.

Power that trusts the people does not fear the people watching. Power that earned victory does not fear verification. Only theatre fears uninterrupted lighting.

History will remember this moment. It will record who demanded clarity and who defended discretion. It will remember who embraced the spotlight and who adjusted the curtains. It will remember who trusted the ballot and who trusted the corridor.

If you are winning, you do not fear the spotlight. You switch it on yourself.

Aare Amerijoye DOT.B

Director General

The Narrative Force