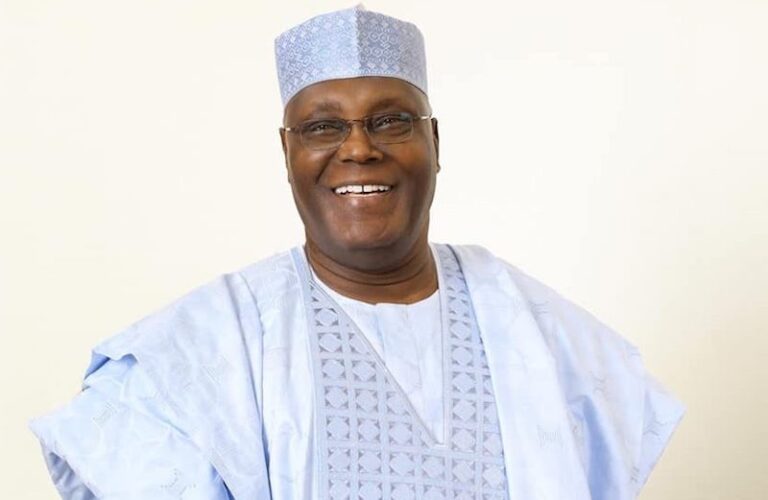

When I sat with Atiku Abubakar and listened to him speak about Nigeria’s unemployed youth, there was no political theatre in his voice, only the kind of quiet gravity that Simone Weil once described when she observed that pain is often the beginning of moral truth rather than a political argument, a sensibility that resonates deeply with Obafemi Awolowo’s lifelong insistence that the purpose of governance is the welfare and dignity of the people.

There was pain.

He spoke not in slogans, but in sentences weighed down by conscience, echoing Hannah Arendt’s warning that a society which fails to honour the labour of its people has already dishonoured itself. He spoke of young Nigerians who did everything society asked of them, went to school, graduated, served their country, only to be abandoned by a system that no longer connects effort to reward, a failure Nnamdi Azikiwe once cautioned against when he argued that political freedom without economic empowerment is an empty victory.

He said, quietly but firmly, that no nation can survive the moral cost of wasting its able-bodied population, a view long captured by Aristotle’s insistence that injustice begins when unequal realities are treated with equal indifference, and by Ahmadu Bello’s conviction that a society that neglects productive labour ultimately undermines its own stability.

Atiku was unequivocal: unemployment is not just an economic failure; it is a breach of trust between the state and its citizens, a breach John Locke warned against when he argued that government is a trust and its holders are merely trustees of the people’s welfare, a position that aligns with Awolowo’s belief that leadership is a moral responsibility before it is a political office.

In his manifesto, employment is not treated as an afterthought or a footnote. It is the spine. He insists that jobs are created not by rhetoric, but by policy coherence, private-sector confidence, industrial revival, decentralised productivity, and an enabling state, aligning with John Stuart Mill’s belief that wealth is nothing more than human energy organised by intelligence, and with Azikiwe’s emphasis on building economic foundations strong enough to sustain national unity. He argues that when government understands its role as facilitator rather than suffocator, wealth follows,and with wealth, employment.

This conviction is not theoretical.

In his private capacity, Atiku has done what many governments have failed to do. He has built enterprises, expanded industries, signed paychecks, and sustained livelihoods. He has watched families depend on payroll stability. He has managed risk, labour, capital, and growth, embodying the principle often attributed to Peter Drucker that leadership is ultimately measured by how many lives remain stable because of the systems one builds, and reflecting Ahmadu Bello’s view that leadership must be judged by the tangible improvement it brings to the lives of ordinary people. He understands employment not as a campaign promise, but as a daily responsibility.

And this is the unavoidable question Nigeria must confront:If a man can create jobs and wealth with private resources, what would he do if entrusted with the resources of a nation, especially when Plato reminds us that power does not change character but merely reveals it, a reminder Awolowo himself echoed when he warned that public office only magnifies the true nature of the officeholder?

There are moments when a nation’s economic failure stops being a policy debate and becomes a human tragedy, moments when spreadsheets collapse into faces and theories dissolve into hunger, what W. Edwards Deming once captured by noting that statistics are merely human beings with their tears wiped away.Moments when national data finds expression in individual despair.

Nigeria is living in such a moment.

Not in abstraction, but in flesh and breath, in the quiet shame of young men who once wore graduation gowns and now wipe dust from their knees before mounting motorcycles at dawn. This is a country where official figures now confirm that youth unemployment and underemployment together trap a staggering proportion of the population, while inflation has climbed to levels that punish labour and reward speculation, a condition Karl Marx warned would arise when labour can no longer sustain the worker, and which Azikiwe feared would erode national cohesion if left unchecked.

Not because Nigerians are lazy.Many rise before sunrise and return home long after night has swallowed the roads, demonstrating what Albert Camus described as exhaustion without progress, a condition that drains dignity rather than builds it, and contradicting Awolowo’s firm belief that Nigerians are industrious when given fair opportunity.

Not because the youth lack education.Degrees hang in rooms where kerosene lamps flicker, certificates wrapped in nylon against humidity and despair, proving Paulo Freire’s argument that education without opportunity is a refined form of cruelty, and reinforcing Ahmadu Bello’s insistence that education must be tied to productive economic outcomes.

Not because the able-bodied refuse to work.They work until their bodies ache, until dignity bleeds into mere survival,illustrating Amartya Sen’s insight that poverty is not the absence of work but the absence of justice in work.

But because leadership has systematically collapsed the bridge between ability and opportunity.

On a humid Lagos morning, somewhere between Agege and Ojodu, a young man named Kunle adjusts his helmet before starting his engine. Kunle is not a mechanic. He is not an apprentice. He is not unskilled. Kunle holds a university degree in Industrial Chemistry. He once dreamed of working in a manufacturing plant, contributing to value chains, earning dignity through productivity, reflecting Kierkegaard’s belief that a person becomes most himself when engaged in the work he was trained to do, a belief Awolowo consistently advanced in his emphasis on productive education.

Today, Kunle ferries commuters on an okada.

Each ride earns him a few hundred naira. Each litre of fuel eats deeper into his soul. Each traffic stop reminds him that he studied not to survive, but to build, a daily confirmation of Oswald Spengler’s warning that when survival replaces aspiration, decline has already begun.

Kunle is not alone.

From Ado-Ekiti to Ilorin, from Minna to Onitsha, from Aba to Ibadan, Nigeria’s streets have become open-air unemployment registers. Graduates in economics, engineering, agriculture, education, and the sciences now negotiate potholes instead of professions. Transport fares rise weekly. Food prices,rice, garri, beans, cooking oil, have climbed so relentlessly that households now ration dignity along with meals, turning hunger into what Frantz Fanon described as a political verdict rather than a natural condition, and fulfilling Azikiwe’s warning that economic despair breeds social instability.

This is not entrepreneurship.

This is economic exile, the very condition Edward Said described as being forced to live outside the life one prepared for.

Under the current administration of Bola Ahmed Tinubu, unemployment has ceased to be an abstract percentage and become a lived emergency. Inflation has eroded wages. Fuel costs have swallowed income. Small businesses collapse under energy costs. Honest labour no longer guarantees survival, a dynamic John Maynard Keynes warned would emerge when prices outrun wages, and which Awolowo believed could only be corrected through disciplined, people-centred economic planning.

An okada rider now earns today to eat tonight. Tomorrow is not planned. Tomorrow is feared.

This is the anatomy of excruciating poverty, the kind George Orwell noted humiliates long before it kills.

Yet this was not always Nigeria’s destiny.

There was a time when leadership understood that employment is the most dignified social programme. When reforms unlocked industries. When policy invited investment. When young Nigerians planned careers, not escape routes, confirming Václav Havel’s belief that hope is born when systems reward effort, a belief shared by Ahmadu Bello in his emphasis on purposeful governance.

That philosophy is what Atiku keeps returning to.

He believes,correctly,that jobs are not created by government offices alone, but by creating an environment where industries can breathe. Where manufacturing returns. Where agriculture becomes enterprise. Where power works. Where states can compete. Where skills meet opportunity, reflecting Friedrich Hayek’s argument that the role of the state is not to replace enterprise but to release it, and echoing Azikiwe’s conviction that economic empowerment is the bedrock of national progress.

The tragedy of today’s Nigeria is not that people are working as okada riders. The tragedy is that they are doing so against their will, against their training, and against their potential, proving that wasted talent is the most expensive luxury a nation can afford, as Awolowo warned when he spoke against the squandering of human capital.

A nation that forces graduates into motorcycles is not innovating.It is retreating.

Atiku’s politics is a refusal to normalise this retreat, and it is here that conscience must rise into prayer, that reflection must turn into supplication, for leadership of this burden cannot rest on strategy alone but must be sustained by grace, a sensibility deeply rooted in the moral traditions espoused by Nigeria’s founding leaders.

He understands that employment is not charity. It is policy. It is planning. It is courage. It is trust in productivity, aligning with Martin Luther King Jr.’s insistence that work is the foundation of dignity, and it is only fitting to ask that God strengthen him with wisdom deeper than ambition, courage greater than fear, and patience anchored in justice, so that compassion never leaves his governance and conscience never yields to convenience.

A Nigeria that works is not a miracle. It is a choice, and choices demand moral clarity, spiritual steadiness, and leaders whose hearts remain open to the cries of the unemployed, the hungry, the humiliated, and the forgotten.

The choice before the youth is stark: accept humiliation as destiny, or insist on dignity as policy. 2027 is not merely an election; it is a generational decision about whether Nigeria will continue managing poverty or finally managing growth, a moment Nelson Mandela would describe as a choice between inheriting fear and creating courage, and it is only right to pray that God guides the conscience of the Nigerian people as they approach it.

Nigeria does not need more okada riders by force.

Nigeria needs jobs by design, and may God restore dignity to labour, heal the wounds of poverty that humiliate before they hunger, and grant that honest work once again guarantees survival and hope in every home.

And that design,tested in private enterprise and ready for national scale, still bears the signature of Atiku Abubakar, and may God bless the works of his hands, grant clarity to his vision, multiply his capacity to generate wealth and employment for the nation, and bless Nigeria with leadership that restores honour to labour and soul to governance.

Aare Amerijoye DOT.B

Director General,

The Narrative Force