There are moments when a nation’s history can only be told truthfully through the pain of its people. Statistics may explain outcomes, but it is human experience that explains consequences. Nigeria has lived through seasons when institutions collapsed so completely that ordinary life itself became an act of courage.

To understand leadership, one must first remember what the absence of leadership feels like.

In 1997 and 1998, banking in Nigeria was not a service; it was a gamble. For millions, the bank hall was a place of quiet terror. People entered cautiously, scanning faces, listening to whispers. A single rumour that a bank was “shaking” could empty an entire branch before noon.

There was the widowed woman in Oshodi who had sold foodstuffs for decades, saving patiently to expand her trade, only to arrive one morning to find her bank sealed,iron shutters down, a notice pasted, armed policemen standing where tellers once smiled. Her life savings vanished without explanation.

There was the retired teacher in Ibadan who deposited his gratuity and pension in what was advertised as a “new generation bank,” only to discover weeks later that the money meant to sustain him till death had disappeared before him.

There were cooperative societies, market women, artisans, transport workers, whose pooled savings evaporated overnight, wiping out hundreds of small hopes in a single stroke.

People cried openly in bank halls. Grown men begged security guards for information they did not have. Some collapsed from shock. Some went home and never recovered.

Fear rewrote behaviour. Salaries were withdrawn the same day they were paid and hidden in biscuit tins, cooking pots, ceiling panels. Nigerians preferred the risk of armed robbers to the certainty of institutional betrayal. Elderly pensioners queued at dawn, not to earn interest, but to ask one desperate question: “Is this bank still alive?”

This was not paranoia. It was memory.

By 1999, when democracy returned, Nigeria’s banking system was not merely weak; it was distrusted. Dozens of banks had failed or were technically insolvent. Insider lending had eaten through balance sheets like termites. Political protection had replaced prudence. Regulation had lost both teeth and credibility. Democracy inherited not optimism, but trauma.

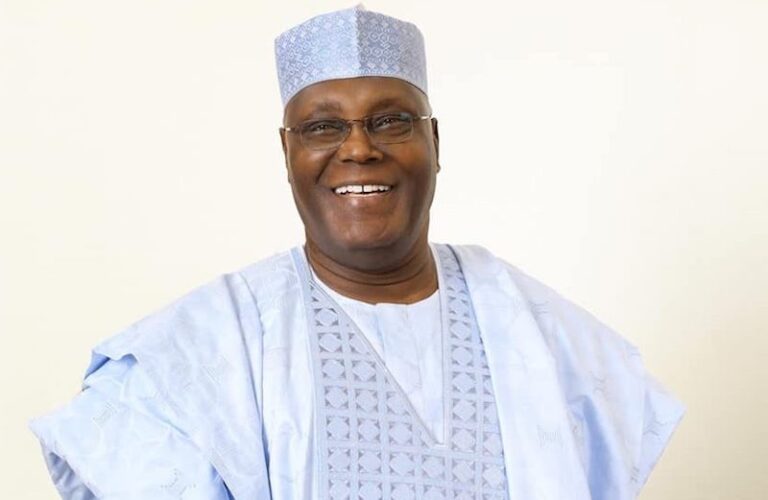

It was into this wounded, suspicious Nigeria that Olusegun Obasanjo and Atiku Abubakar stepped, not to applause, but to repair.

They did not begin with spectacle. They began with discipline. Distressed banks were confronted, not cosmetically preserved. Regulatory authority was restored. Deposit insurance was strengthened so that failure would no longer translate into total personal ruin. Political connections ceased to be sufficient excuses for recklessness.

These decisions were painful. Banks closed. Shareholders lost money. Politicians protested. But something subtle and profound began to change. People started leaving money in their accounts overnight. Traders resumed credit relationships. Pensioners stopped queuing merely to confirm survival.

By the early 2000s, the fear that had defined banking life in the late 1990s had begun to loosen its grip. Only then did consolidation become possible,not as emergency surgery, but as the final stage of recovery.

This sequence matters. Consolidation did not rescue a corpse; it completed the rescue of a stabilised patient. It was proof of leadership that understood that reform begins with trust, not theatre.

The same philosophy guided the telecommunications revolution. Liberalisation was pursued when it was unpopular, resisted by monopolies, and dismissed by sceptics. Today, mobile phones sit in every hand, digital businesses thrive on every street, and millions earn livelihoods from systems born of those courageous decisions. What was once controversial is now ordinary life.

This is what it means to be tested.

Now, fast-forward to the present.

Under Bola Ahmed Tinubu and the All Progressives Congress, Nigerians are once again learning the language of pain, this time without a visible plan of rescue.

Today, the suffering is different, yet hauntingly familiar.

A civil servant watches his salary lose value between payday and the bus stop. A trader prices goods in the morning and reprices them by evening. Parents withdraw children from private schools mid-term, not because they despise education, but because survival has become urgent. Businesses shut down not from mismanagement, but from policy shock. Savings are quietly eaten by inflation. The naira bleeds in public view. Confidence evaporates daily.

Unlike the late 1990s, banks are standing but life is collapsing around them.

Queues have returned, not for withdrawals, but for food. Fear has returned, not of bank failure, but of tomorrow itself. Nigerians are again hiding, this time not cash, but hope.

The cruelty of the present moment lies in its irony: this suffering is not inherited from military chaos; it is manufactured under civilian authority. It is not the absence of policy, but the recklessness of it. And unlike the Obasanjo-Atiku era, there is no visible sequencing ,no stabilisation before sacrifice, no reassurance before pain.

Leadership is not measured by how loudly it demands endurance from the people, but by how carefully it manages their suffering.

This is why memory matters.

Atiku Abubakar has governed Nigeria when things were falling apart and helped steady them. He has seen depositors cry, businesses collapse, and trust die and he has participated in the hard, unglamorous work of restoring it. He understands that reform without compassion becomes cruelty, and sacrifice without sequencing becomes punishment.

Nigeria does not need another experiment conducted on the backs of the poor. It needs steadiness born of experience,judgment refined by consequence, and empathy forged in crisis.

That is why the record still speaks.That is why the contrast is unavoidable.

Atiku Abubakar was tested during Nigeria’s hardest economic collapses, and trusted to lead recovery when it mattered most.

And in a nation once again crying for stability, the evidence insists,he is still going strong.

Aare Amerijoye DOT.B

Director General

The Narrative Force