An analysis of Nigeria’s place on the IMF’s projected growth contributors list, and the uncomfortable truths the government would rather ignore.

By Kunle Oshobi

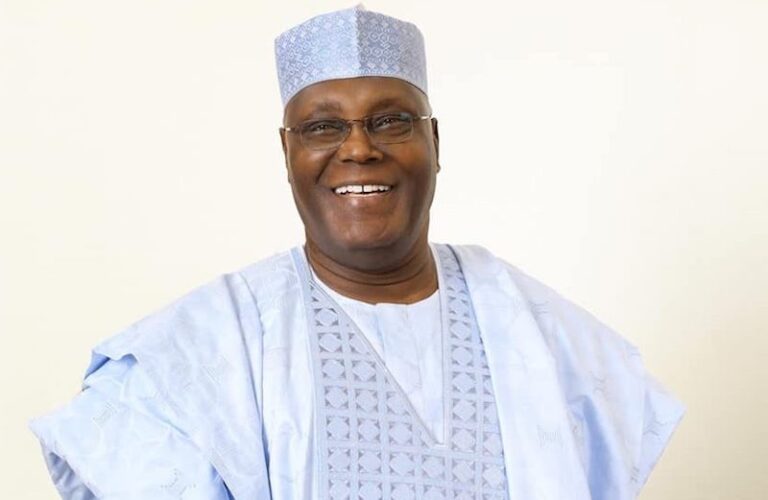

There is a particular kind of political opportunism that thrives on the ignorance of a public that does not fully understand how macroeconomic indicators work. The Nigerian government demonstrated this quite convincingly in the past 24 hours. When the International Monetary Fund released data projecting the top 10 countries that would contribute most to global economic growth in 2026, the Tinubu administration wasted no time in wrapping itself in the achievement, as though ranking sixth on an IMF projection list were somehow the product of deliberate policy genius. Around the same time, the Naira recorded a marginal appreciation against the dollar, and the machinery of government spin went into overdrive, linking both developments to the economic reforms of President Bola Tinubu. Both claims collapse under scrutiny.

The IMF List: It Is About Size, Not Skill

To understand why Nigeria made the IMF’s list, you do not need to understand Nigerian economic policy. You only need to understand one thing: the list is a function of a country’s economic size, multiplied by its projected growth rate. The IMF calculates each country’s contribution to global growth by weighting its domestic GDP growth rate against its share of total world output, measured in purchasing-power-parity terms. A large economy growing at a modest pace will outperform a small economy growing at a blistering pace, simply because more economic mass is in play.

Nigeria’s economy is the largest in Africa, a fact that predates Tinubu, predates APC itself, and will outlast both. The country did not earn its place on this list through clever reform or visionary governance. It earned it because of its sheer economic weight. For context, Germany, one of the most sophisticated industrial economies on the planet, ranks tenth on the same list, contributing just 0.9 percent to global growth. Nigeria’s projected 1.5 percent share does not mean Nigeria is outperforming Germany. It means Nigeria is relatively bigger.

China leads at 26.6 percent, India follows at 17 percent, and together the two account for over 43 percent of all global economic growth in 2026. Nigeria is a footnote in that narrative, not a headline. To celebrate its inclusion as evidence of Tinubu’s economic acumen is to mistake the scoreboard for the strategy.

The Naira’s Marginal Appreciation: Thank Dangote, Not Tinubu

The second claim doing the rounds is that the Naira’s recent appreciation vindicates the administration’s exchange-rate reforms. The reality is considerably less flattering.

The Naira strengthened to around ₦1,394 to the dollar in late January 2026, its strongest since May 2024, following a period in which it traded as high as ₦1,554 in August 2025. The appreciation is real but marginal, and it did not happen because of government policy. It happened largely because of the Dangote Refinery.

For nearly three decades, Nigeria imported the bulk of its refined petroleum products, requiring billions of dollars annually, putting relentless downward pressure on the Naira (fuel imports was responsible for 30% of Nigeria’s import bill). The Dangote Refinery, with its 650,000 barrels-per-day capacity, has altered this dynamic. Petrol import bills dropped from ₦3.81 trillion in Q1 2024 to ₦1.76 trillion in Q1 2025 as local production ramped up, and Nigeria has even begun exporting refined products. The IMF estimates the refinery will improve the balance of payments by $5.5 billion annually.

This is a private-sector achievement, a $20 billion investment by Aliko Dangote that survived delays and regulatory battles long before Tinubu came to power. The government did not build, fund, or meaningfully facilitate this refinery. The Naira’s gains are also partly driven by broader global dollar weakness benefiting emerging market currencies. To allow the government to claim credit here is to hand a politician the trophy for a race he did not run.

The Poverty Crisis the Government Does Not Want to Talk About

While the administration celebrates IMF rankings and exchange-rate movements, 139 million Nigerians are living in poverty. That figure comes from the World Bank, released in October 2025. When Tinubu took office in May 2023, the number was approximately 87 million. In less than two and a half years, over 50 million additional Nigerians have fallen below the poverty line. The poverty rate has risen from roughly 38.9 percent to an estimated 46 percent, and the World Bank projects it will climb to 62 percent by 2026.

The causes are directly traceable to decisions made by this administration. On his first day in office, Tinubu declared the fuel subsidy “gone.” Fuel prices surged from ₦198 per litre to over ₦1,000, a hike of more than 400 percent. Because petroleum products underpin nearly every cost in the Nigerian economy, transportation, electricity generation, food distribution, the shock radiated through the entire system. Food prices rose fivefold between 2020 and 2024, and inflation hit 34 percent, an 18-year high. The decision to float the Naira without any safety nets compounded the damage; the currency collapsed from ₦460 to nearly ₦1,465 by late 2024, devastating purchasing power further.

In August 2024, hunger protests erupted across the country, lasting ten days before being suppressed by security forces, with at least 24 people killed. The World Food Programme warned that Nigeria had never seen so many people without food. An Afrobarometer survey found that 93 percent of Nigerians believe the country is going in the wrong direction, and only 3 percent rated the government positively on keeping prices stable.

The Illusion of “Turning the Corner”

In his Independence Day address in October 2025, Tinubu told Nigerians the country had “turned the corner” and that the sacrifices of the past two years were “beginning to yield measurable results.” The World Bank’s Country Director for Nigeria responded within days by reiterating that 139 million Nigerians were in poverty and that the central challenge remained translating stabilisation reforms into better living standards for all.

This is the uncomfortable truth no amount of spin can obscure: macroeconomic stability and poverty reduction are not the same thing. A country can have a growing GDP, a stable exchange rate, and falling inflation while simultaneously pushing tens of millions of its citizens deeper into destitution. Nigeria is living proof. The Tinubu administration has confused the instruments of economic management with the purpose of economic policy. Stabilising the Naira and achieving positive GDP growth are means to an end, that end being the improvement of ordinary Nigerians’ lives. By that measure, this administration has failed, spectacularly and measurably.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s inclusion on the IMF’s list reflects the country’s demographic and resource-driven economic weight. The Naira’s appreciation is a testament to the Dangote Refinery’s impact on the trade balance. Neither vindicates Tinubu’s policies.

Meanwhile, the number of Nigerians in poverty has grown by more than 50 million since he took office. A government that celebrates its ranking on an international list while 139 million of its citizens live in poverty is not a government that has turned any corner. It is a government that has learned to mistake the map for the territory, and hopes no one notices the difference.

Kunle Oshobi is the Head of Planning and Strategy of the The Narrative Force