Aare Amerijoye DOT.B.

Those who profit from Nigeria remaining broken.

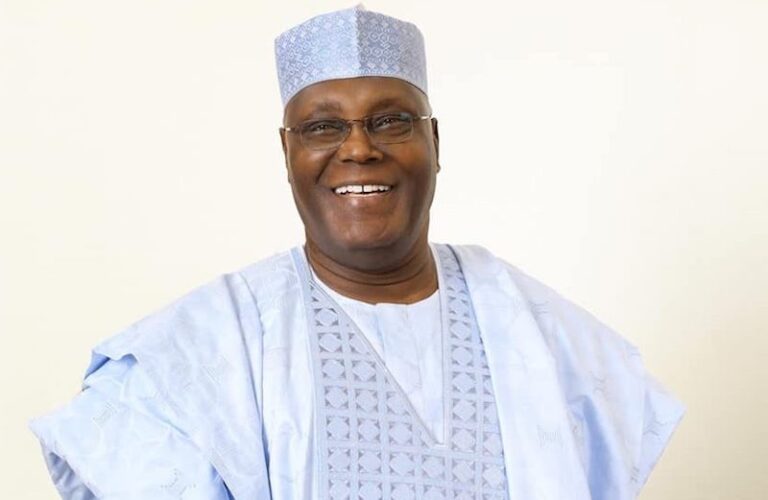

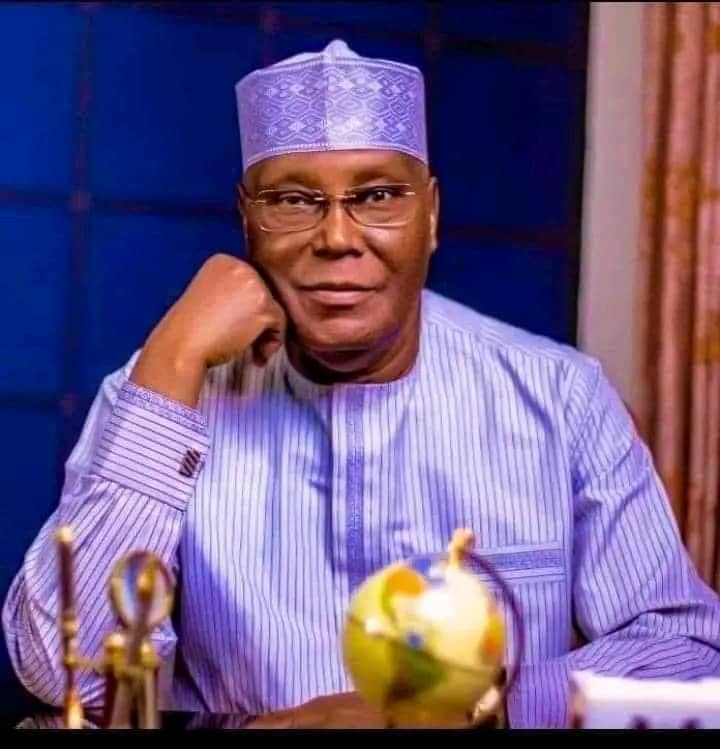

Not the ordinary citizen struggling with food prices. Not the graduate trapped between certificates and joblessness. Not the trader suffocating under policy chaos. The anxiety surrounding Atiku Abubakar belongs to a narrower constituency: beneficiaries of dysfunction, custodians of institutional weakness, and merchants who convert state failure into private advantage.

Atiku unsettles them because he represents an anomaly in Nigerian politics — a public figure whose record can be interrogated without mythology. His political life does not depend on mysticism, folklore, or emotional theatrics. It is anchored in policy decisions, structural reforms, and measurable outcomes. In a system where ambiguity is often weaponised as protection, clarity becomes dangerous.

The clearest illustration remains the telecommunications revolution. Prior to Atiku’s tenure as Vice President, Nigeria’s telephone system was a monument to stagnation: scarce lines, endless waiting lists, suffocating inefficiency, and an economy haemorrhaging productivity. Under the reformist thrust he championed within the Obasanjo administration, the sector was liberalised. Monopoly was dismantled, private capital invited, competition enforced, and regulation institutionalised. What followed was not incremental improvement but transformation ,explosive growth in connectivity, millions of new lines, mass employment, and the birth of Nigeria’s digital economy. Fintech, e-commerce, tech startups, remote work, and modern service delivery all trace their roots to that single policy choice. That is not rhetoric; that is consequence.

This is why fear follows his name. Those who survive on patronage rather than productivity understand that competence, once armed with authority, is existentially threatening. Serious governance collapses rent-seeking ecosystems. Order suffocates chaos merchants.

Equally unsettling to his opponents is Atiku’s national breadth. He is not a sectional candidate assembled through ethnic improvisation. In the South-West, his market-driven philosophy aligns naturally with enterprise culture and private-sector logic. In the South-East, his long-standing bridges, inclusionary posture, and respect for commerce resonate deeply with a region historically marginalised yet economically indispensable. In the South-South, his grasp of federalism, equity, and development partnership speaks directly to long-standing questions of fairness and resource justice. In the North, his roots, experience, and stabilising presence offer continuity without regression, identity without extremism. Few Nigerian politicians command such acceptance across regions without resorting to tribal performance.

It is therefore no accident that attacks against him rarely engage policy. They retreat instead into distortion, emotional baiting, and propaganda noise. Performance is uncomfortable terrain for those with little to defend. Atiku’s presence drags politics back to an unforgiving arena ,records, comparisons, competence, and outcomes.

Notice what his adversaries are not afraid of. They are not afraid of slogans. They are not afraid of social-media hysteria. They are not afraid of fan-base skirmishes. They are afraid of a serious national conversation one in which governance is stripped of excuses and failure can no longer hide behind identity.

History has always been cruel to systems that profit from decay. Reformers do not merely challenge power; they expose it. The persistent unease surrounding Atiku Abubakar is therefore not accidental, it is diagnostic. It reveals a political order that understands, perhaps better than it admits, that it cannot survive sustained scrutiny.

That, ultimately, is who is afraid and why.

Aare Amerijoye DOT.B,

Director General,

The Narrative Force